Pamela Merritt

August 10, 2015

Martha Reben was one tough lady. She came to the Adirondacks at the age of twenty-one, to cure in the famous tuberculosis sanitarium in Saranac Lake. But after three-and-a-half years, it looked like she was losing. Her condition was described as "severely debilitated" and she was facing a procedure of last resort where ribs were removed to collapse a lung.

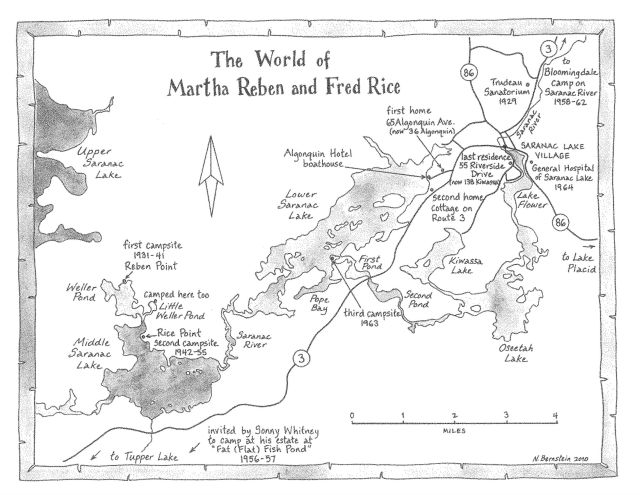

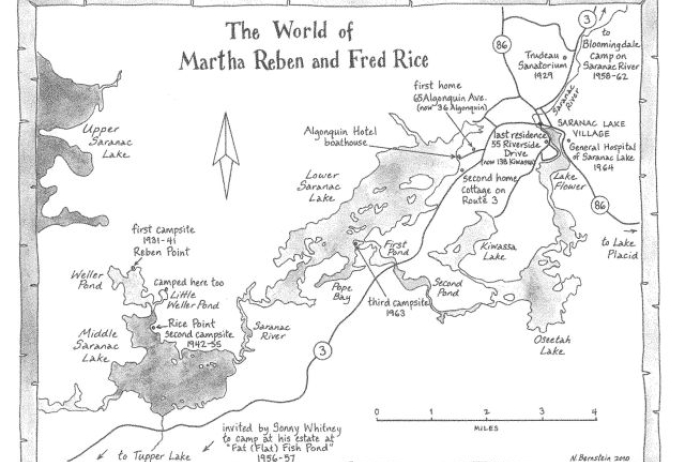

At this same time, 1931, Adirondack Guide and boat builder Fred Rice had placed an ad in the local paper. "Wanted: To get in touch with some invalid who is not improving, and who would like to go into the woods for the summer." This was the result of Rice's own observations and convictions, and his respect for the work of minister William Henry Harrison Murray, aka Adirondack Murray. Both felt that getting out in the woods was even better than the treatments available indoors.

Blind date with destiny

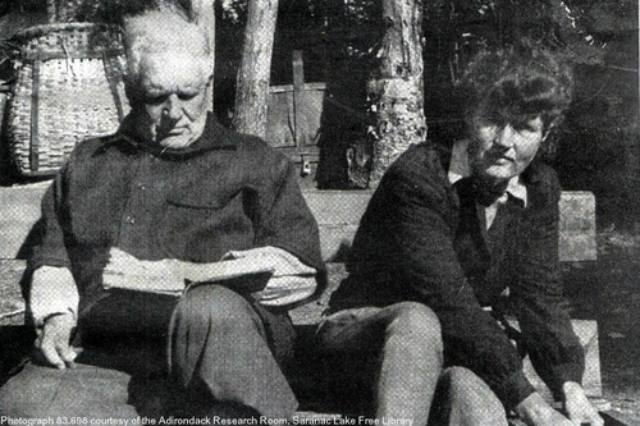

Mr. Rice had not expected such a gravely ill young woman to answer his notice; he was thinking more of a sportsman who was used to roughing it. But, as serendipity would have it, Martha's was the only answer to his ad... and she had used her first initial, so he'd been expecting a man. As Martha would write, twenty years later, "...he decided in his forthright way that I would have to do." So the two of them set out to camp in the woods all summer.

Destination Weller Pond, with equipment consisting of a tent, a stone fireplace, a rough table and no chairs. She didn't mind the cast off cooking equipment from Mrs. Rice's kitchen, but she did mind the corn being served in an "under the bed" form of crockery. This was a "roughing it" line she had no trouble drawing.

Still, what happened there was amazing. Martha got better. She was to write three books, based on 20 years of journaling about the Adirondack wilderness. The first one, "The Healing Woods," was a bestseller.

She was born Martha Rebentisch (author's name shortened on the suggestion of her publisher) in 1906, in New York City. When she was six she lost her mother to the Great White Plague: tuberculosis. As a teenager she developed the disease, and went from Pennsylvania, the Catskills, and finally to Dr. Trudeau's famous San. But after three operations, she was still suffering from deteriorating health.

So she left Trudeau Sanitarium "against medical advice." At least, that is what the old, handwritten records say. But in truth, Martha and Fred were actually testing out the final step in Dr. Trudeau's theories. He believed in social support, a home-like atmosphere, and as much fresh air as the patient could stand.

After all, it was Dr. Trudeau who had been moving away from curing people in the sanitarium. He was letting those who did not need constant nursing move further from the San. First there was Little Red (above, interior) a tiny cottage where two people could rest and sit on the postage-stamp porch. This expanded into the practice of settling patients into homes for constant support and care.

Dr. Trudeau had been a pioneer in the early recognition of psychological factors in fighting disease and illness. This had led him away from institutionalized care and towards an approach that, more and more, harnessed Nature herself as a team member in the cure process. After all, Dr. Trudeau himself had come here in 1873 to die from tuberculosis, choosing a favorite place for what he thought would be his last days. Instead, it was a rebirth, both as a man and as a healer.

Taking it to the limit

This is what Martha Reben, with few other options, decided to explore. She must have felt she had nothing to lose by going further into nature. But the bravery required for this particular step must have been considerable.

She knew very little of what she was getting into, having grown up in a big city and spending much of her time bedridden. She placed her trust in the considerably older and, in the ways of the woods, wiser, Fred Rice. They set off for the eight-mile distant Weller Pond.

Martha and Fred spent the spring, summer, and fall on remote Weller Pond for the next six years. In the winter she would move in with her guide and his wife, Kate. The three of them would forge an enduring friendship. In her series of books, "The Healing Woods" (1952), "The Way of the Wilderness" (1954), and "A Sharing of Joy" (1963), Martha would describe the simple routines of their day, from the making of backwoods meals to the teaching of woodcraft. Fred was often absent as he took guiding jobs, and she would have plenty of solitude for thinking and writing.

She also described the slowly increasing sense that she and Fred had made the right call. She was getting better. She was never to be a robust person, and her death in 1964 would be from congestive heart failure, which could have come about from the strain of breathing with compromised lung function.

A long shot that paid off

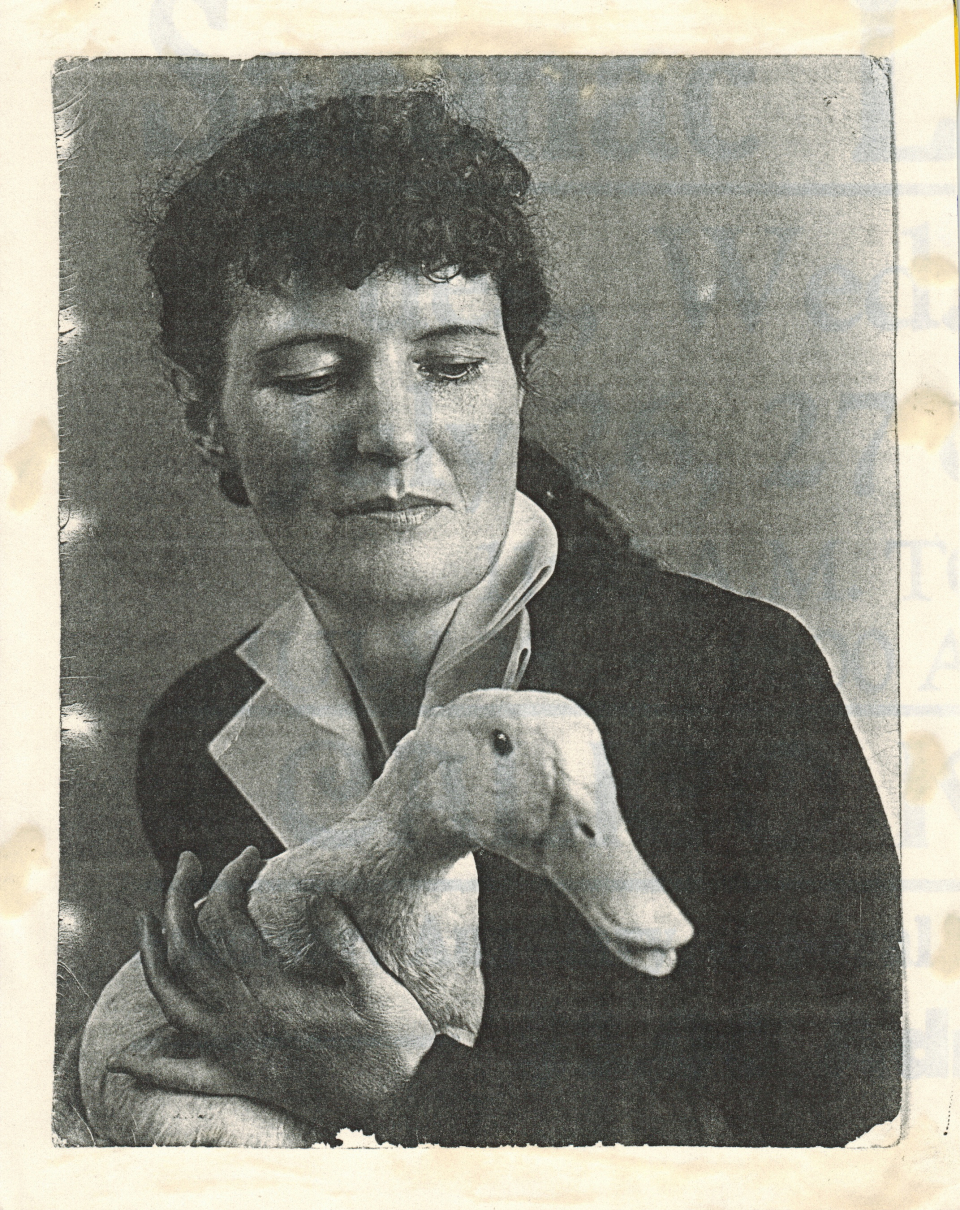

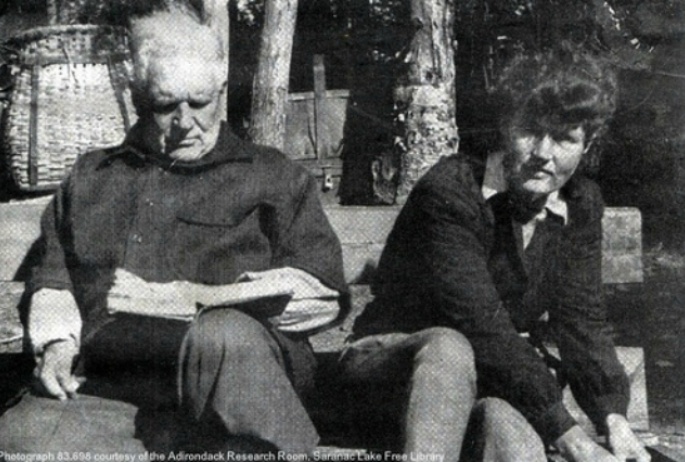

A photo of her that first summer showed a drawn young woman, her lap and legs covered with a blanket and her hair lying limply against her head. This was a marvelous contrast to a later photo, where her hair is lush and full, and her legs are in pants, and her posture indicates a readiness to get up and go.

This small miracle stayed local until the publication of her first book, in 1952. It became an extraordinary bestseller that revived interest in the area, and in natural healing. The money she got for the film rights to the book (which was never made) was enough for her to buy a small, rustic, camp on the Saranac River. It was enough for her to have a place of her own to call home, since she never returned to live in New York City.

During one visit, she recalled, "I found the clanging of streetcars, blaring taxis and rattling trucks almost deafening." Each spring, summer, and fall she would spend in the wilderness, and each winter with her friends Fred and Kate and her pet duck, Mr. Dooly.

Her third book was published just months before her death in 1963, and her fourth, rumored to be completed but never seen, is considered lost. While she never considered herself in robust health, never quite getting over the years of curing, the operations, and the effects of her tuberculosis, she celebrated every year since a frail figure slipped into Fred Rice's boat in 1931.

That young lady's odds had not been good.

On Thursday, June 11, 1964 at precisely 2:30 p.m. a plane scattered Martha's ashes over Weller Pond, so she need never leave. Today, there are five public campsites on Weller Pond, which are part of the Saranac Islands Public Campground. Weller Pond still has a lean to. The view from the waters of Middle Saranac Lake still shows Ampersand Mountain framed against the sky.

The subtitle of Martha's first book, "How my search for health in the woods opened up a new way of life," summed up everything she had hoped to accomplish. For herself, and for others.

Explore our many ways of wellness. Let someone cook for you at one of our dining spots. Find your own spot in the healing woods.

To learn more about Martha Reben, visit the Historic Saranac Lake local Wiki. This is a fantastic resource for exploring the history of the Saranac Lake region.

Packages and Promotions

Valid May. 1

- Oct. 31

Valid Dec. 6

- Nov. 1

Zip and Whip Expedition

Farmhouse UTVs

Experience Outdoors and Farmhouse UTVs have teamed up to bring your family and friends the Adirondack adventure you've been waiting for....

Valid Dec. 1

- Dec. 1

Valid Dec. 1

- Dec. 1

Linger Longer in Saranac Lake

Best Western Saranac Lake

Linger Longer in Saranac Lake at our supremely located property, Best Western Saranac Lake. Stay 2 nights or more and get 15% off!

Valid Jun. 20

- Sep. 7

Valid Mar. 12

- Jun. 30

Guided Nature Immersions - 10% off for Pre-Season Registration

Adirondack Riverwalking & Forest Bathing

Picture it now...you are wading the Ausable River on a warm summer day, feel the cool water against you, hear the sounds of the birds and the...

Valid Jan. 21

- Jan. 21

Valid Jan. 21

- Jan. 21

Stay and Dine

Voco Saranac Lake

Receive a 50 dollar credit per stay to use in our Boathouse Saranac Lake Pub. Enjoy an exceptional dining experience with unparalleled views great...

Valid May. 1

- Nov. 2

Valid Apr. 1

- May. 1

Forest Bathing Guided Experience - 10% off for pre-season registration

Adirondack Riverwalking & Forest Bathing

Guided forest sensory immersion walk for all. Sign up early for 10% off!