When among the millions of acres of Adirondack wilderness, we feel close to the natural world. Once visited, it has a magnetic pull on our heart which encourages us to return.

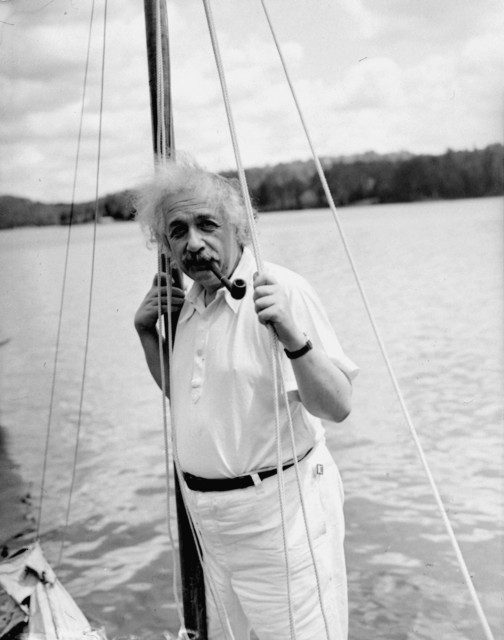

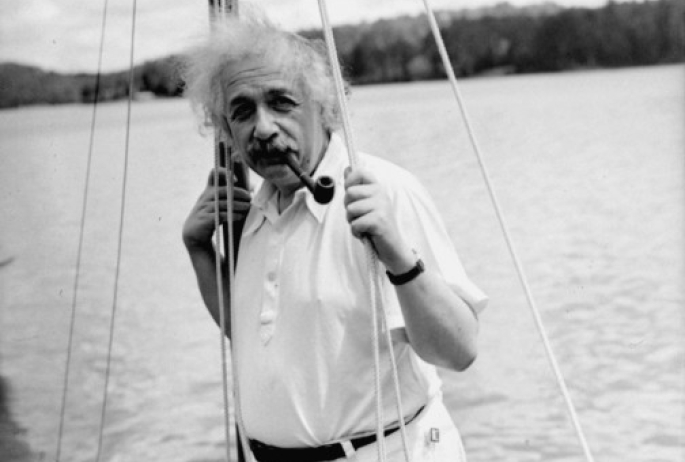

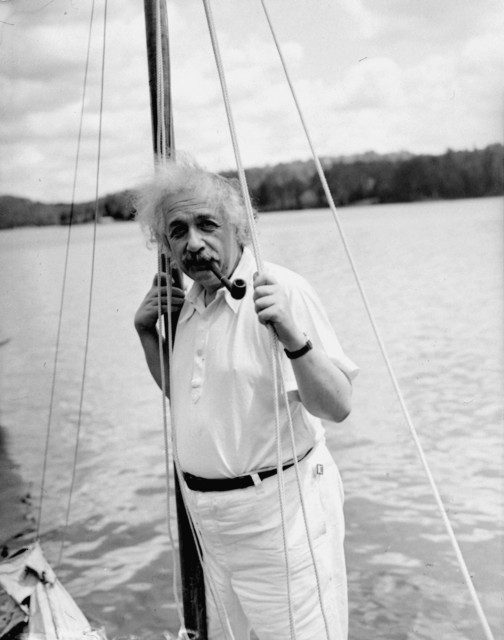

This principle is embodied in a famous visitor. When I married a Saranac Lake native, his older relatives loved to tell me stories about the man in baggy trousers and wild hair, who always had a smile for the children he met. Not only was he a friendly face in town, he was encountered fairly often out on Lake Flower, where he combined a love of sailing... with an inability to swim.

He was Albert Einstein.

"Someone was always fishing him out," I was told. Most famously, Don Duso, local business owner, village fire chief, and long time chairman of the Saranac Lake Winter Carnival Committee, saved the day when he was only ten. Einstein's sailboat overturned on Lonesome Bay, and Don dove under the capsized craft to free Einstein's foot from the rigging.

Don Duso, and his childhood friends, might have changed a bit of history because they looked after their famous friend so well. This rescue took place in the summer of 1941. One of Einstein's most fateful acts had taken place only a couple of years before, when he had written a fateful letter to then-President Roosevelt, to inform him that an atomic bomb was now theoretically possible. If so, we had to get there ahead of the Nazi regime in Germany.

So while Don and his friends would not have changed that part of history, they did make possible the famous article published in 1950. Einstein described his "unified field theory" in a Scientific American article entitled "On the Generalized Theory of Gravitation." This knotty problem is still being debated today!

"We all offered to teach him to swim, but he just didn't seem to worry about it," my new relatives said, remembering those pre-war times. Einstein had once remarked that he liked sailing because it "demands the least energy." Friends who sailed with him noted his fearless delight in the unexpected, and his seeming indifference to danger.

These might have been the very qualities that led to his groundbreaking work in theoretical physics. Famously, his method was not one of painstaking math on a blackboard, as he is so often portrayed. That came later. His breakthroughs began almost entirely in his imagination, as he visualized himself riding light waves or moving through space close to the speed of light. Once he came to certain conclusions using these highly fanciful techniques, he would then work on the scientific proofs he could share with other physicists.

Einstein's fame, and highly distinctive appearance, led to many street encounters where people would stop him on the street and ask him to explain his theory. As a polite and humble man, Einstein would handle such inquiries with, "Pardon me, sorry! Always I am mistaken for Professor Einstein."

His easy acceptance in the village life of Saranac Lake must have appealed to him as much as the lovely lakes did. From his first visit in 1936, to hearing of the atomic bomb's detonation in the summer of 1945, on the radio in Knollwood's Cabin Six, he would return again and again. Reporter Richard Lewis, an Albany Times Union reporter who was first to interview him on this momentous occasion, quoted him thus: "In developing atomic or nuclear energy, science did not draw upon supernatural strength, but merely imitated the reaction of the sun's rays. Atomic power is no more unnatural than when I sail my boat on Saranac Lake."

Perhaps the Park is a source of power, to judge from the many famous folk, from Robert Louis Stevenson to Bela Bartok, who have done creative work here.

If so, it is the kind of power accessible to everyone.