July 16, 2018

Submitted by guest writer Carol L. Douglas

It’s the wilderness that draws us, so we draw the wilderness.

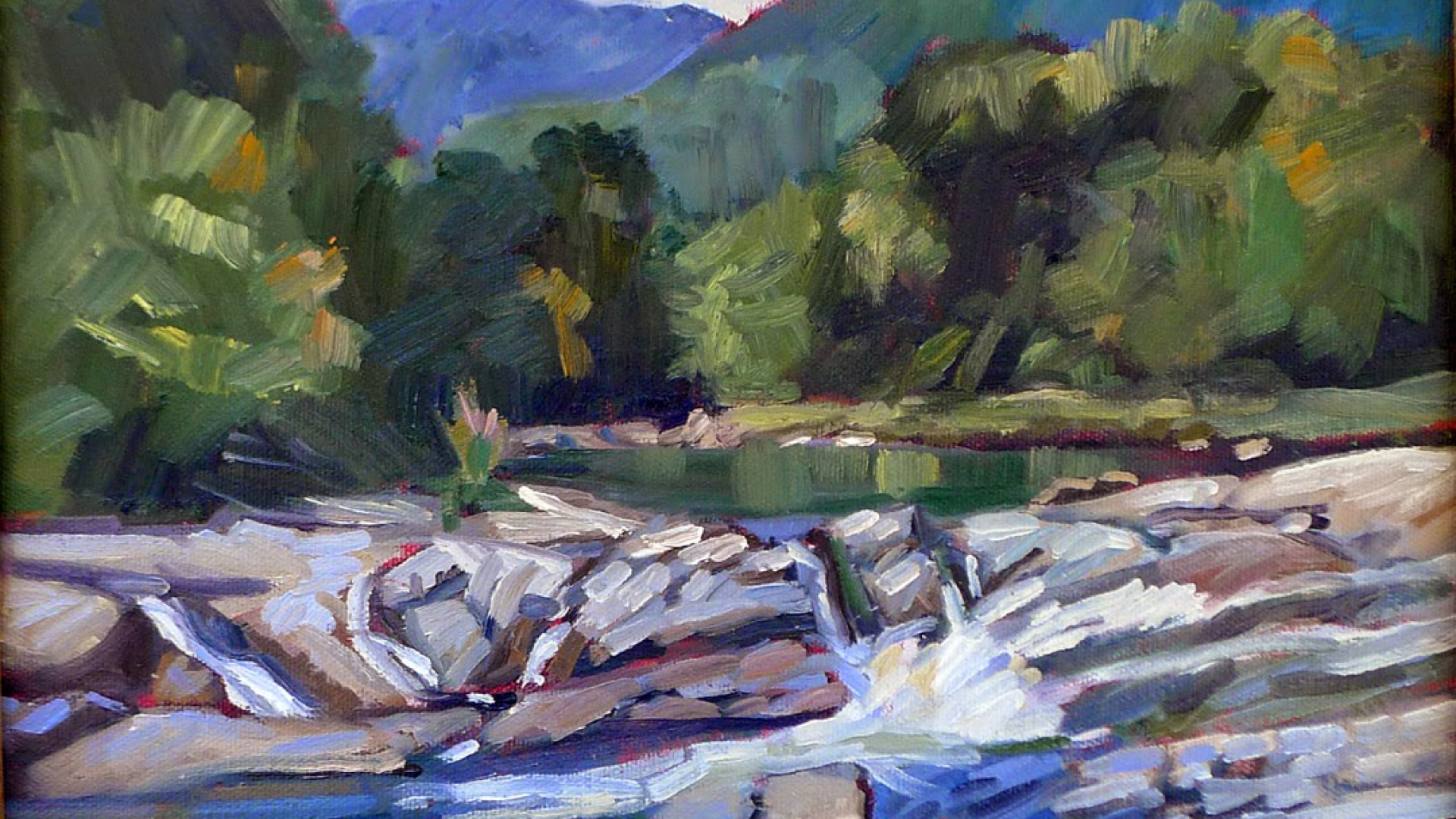

I’ve painted in tough locations, including on the deck of an ocean-going schooner, in the desert, and above the Arctic Circle. Yet there is no place more exciting or challenging for the plein air painter than New York’s Adirondacks. The landscape dares the painter to leave his car and hike or paddle in search of the perfect view. It is always just around the next bend or on the next lake.

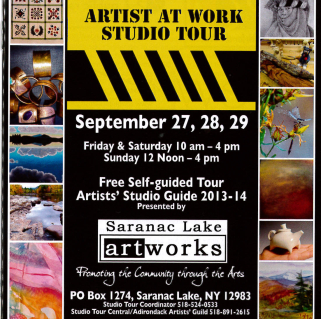

At the same time, roughing it isn’t everyone’s style. A painter can still achieve stellar results working from the roadside. Practically speaking, painters at the tenth annual Adirondack Plein Air Festival, August 13-18, will do both. Some of us will wander along the trails at Paul Smith's VIC in search of bog flowers, or hike to rocky outcrops along the Wilmington Flume. Others will paint street scenes in downtown Saranac Lake.

The Adirondack Plein Air Festival has grown in stature over the past decade. This year, fifty artists from as far as Ireland, California, and Georgia will participate. They were juried in by a panel of three professional painters, so the standards are high. If you’re an art lover or budding artist and have wondered what plein air painting is all about, this is an opportunity to watch and learn. Joe Gyurcsak is teaching a workshop right before the festival. You can also find painters along the trail and watch them work. Most of us are happy ambassadors for our craft.

The event ends with a show and sale at Saranac Lake Town Hall. Tickets for the Friday, August 17 preview reception can be purchased online, or you can pop in on Saturday between noon and 5 p.m. I’ll be there, with 49 of my closest friends.

What is plein air?

Plein air simply means painting outdoors from life. The English painter John Constable is credited with inventing it. The Impressionists made it legit. Modern plein air festivals originated in California in the 1980s. There are now hundreds of events nationwide. Participants generally work in oils, acrylics, watercolors, or pastel.

The plein air painter works outdoors in all sorts of weather, making false starts and trying to outrace fading light. We leave the security of our studios behind for the uncertainty of nature. The results are fresh, juicy, and unpredictable. Often, we work alone. In events like Adirondack Plein Air Festival, we have the additional pressures of strict time limits and competition for prizes. For all that, we’re a pretty congenial bunch, happy to work side-by-side with old friends for the few days of the festival.

The ADK is at the heart of plein air history

The nineteenth century was a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization. That meant lights, trolleys, and skyscrapers, but it also meant smog, noise, disease, and overcrowding. As cities grew, people began to long for a return to an untouched Eden. The dark mystery of New York’s great mountain ranges—the Catskills and Adirondacks—caught the popular imagination. This was largely the doing of the Hudson River School artists and their followers.

Painting in the wilderness wasn’t easy. Prior to the opening of the Adirondack railroad in 1871, the northern part of the state was desolate and forbidding. It was the province of trackers and trappers. The only way in was along rough trails or chains of rivers.

Thomas Cole and Asher Durand were sketching in the Adirondacks by 1837. Thomas Cole’s Indian Pass (c. 1847) was painted in Tahawus, near Newcomb, now a ghost town. Alexander Wyant’s The Flume (c. 1875) captures a stretch of the nearby Opalescent River.

Winslow Homer’s Two Guides (1877) was painted in the Keene Valley. In a recently-felled clearing on an autumn day, an old guide instructs his young partner. As with all Homer’s paintings, it speaks on many levels. One of his points was the transformation of the old wilderness into a new, more accessible one.

It’s still untamed, of course. At more than six million acres, the Adirondacks include 10,000 lakes, 30,000 miles of running water, 46 High Peaks, and innumerable bogs, rock formations, and rare plants. It is a place of infinite variety. I’ve painted in Canada’s storied Algonquin Provincial Park, made famous by Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven painters. The Adirondacks are tougher, higher, just as watery, and every bit as isolated.

The weather runs from glorious to glowering and back again in minutes. I’ve painted in snow in May and sunshine in February. The air can be hot and close, or it can splash out in wild pyrotechnics. All that weather against sheer rock walls and mountain lakes makes for painting drama.

In some ways, modern painters have the same access problem as our ancestors. Bushwhacking is hard work. There are, in fact, fewer roads today than when the Adirondacks was extensively logged. It’s hard to reach the place where The Flume was painted, since it’s not anywhere near a modern road. Painter Sandra Hildreth has done it. “It’s a long, long hike!” she told me.

We still have to take our equipment to the view. However, we have great advantages in materials. Until the late twentieth century, painters used heavy wooden paint-boxes and easels. I now have a lightweight aluminum paint box that sits on a carbon fiber tripod. My watercolor kit is even more efficient; I can slip it into a large pocket. I have an aluminum canoe, lightweight trail boots, and telescoping hiking poles. Even my water bottle is made of plastic.

And of course, we have cars. My painting car is a 2005 Toyota Prius. It has logged more than 260,000 miles, mostly on backroads. Not only does it provide transportation, its hatchback makes a shelter for when it pours.

How do we make our paintings?

Every painting starts with reconnoitering. For some artists, this means taking photos with a cell phone. I prefer to choose a trail or area and sit down to absorb the atmosphere. Then I use a sketchbook to investigate what is important and visually appealing in the vicinity. Only when I’ve nailed that down do I set up my easel and get to work.

It’s hard to predict how long a painting will take. Sometimes I return to the same place over several days. My friend Crista Pisano does tiny, jewel-like pieces that are only a few inches across. They take her many hours. But as a general rule, I can paint a 12-by-16-inch field painting in three or four hours.

There are always interruptions. It may rain, or something may happen to obscure our view, or a moose may wander by. We try to paint during every daylight hour. The Adirondack Plein Air Festival includes a nocturne category, so we will be painting at night as well.

That means we carry water and snacks along with our gear. I also have a compass. That’s not to find my way home, but to figure out where the sun is heading.

The etiquette for plein air painting is much the same as for hiking and camping. Watch where you put your feet. Don’t stomp the foliage. Look out for poison ivy. Stay well off trails so others can get through. Dispose of your own trash (pack it in, pack it out). If you need to pee, stay away from trails, waterways, and campsites. Check yourself for ticks. Tell someone where you’re headed, and make sure your phone is charged.

The painter must also police the area carefully when leaving. We love the places we paint, so we try to never leave dirty painting rags, turpentine, or pigments in the forest.

Painting from a car

After two decades of ranging around on foot, this is the year when I’m most interested in roadside painting. I had foot surgery in April and have been in a boot or on crutches almost continually.

I’m not worried. There are many roadside spots that make for beautiful paintings. During the festival, look for painters at the river turnouts, on the shores of Lake Colby, in the Harrietstown Cemetery, at night painting reflections on Lake Flower, and many other places. Plein air painting isn’t in the difficulty of the experience, it’s in the beauty of the place.

Going to the festival? Make it a vacation and plan to stay with us. There are plenty of attractions and great restaurants to enjoy in the region.

Carol L. Douglas was born in Buffalo, NY, and now lives and works in Rockport, ME. She has painted worldwide and taught in the Adirondacks, Maine, New Mexico, and elsewhere. Her blog, Watch Me Paint, is the seventh-ranked painting blog on the internet.

Packages and Promotions

Valid Jan. 21

- Jan. 21

Valid Jan. 21

- Jan. 21

Stay and Dine

Voco Saranac Lake

Receive a 50 dollar credit per stay to use in our Boathouse Saranac Lake Pub. Enjoy an exceptional dining experience with unparalleled views great...