Pamela Merritt

October 27, 2015

There are many Halloween tales to be told in our corner of the Adirondacks. Some are well-known and some are well-hidden. This particular spooky bit of history is very obscure, even in Saranac Lake. The most well-known figure in the story, John Brown, actually rests in peace at his Lake Placid farm.

But he does not rest there alone.

a bizarre proposal

If a stranger asked if they could send you some bodies, would you agree? Most people might not. But in Saranac Lake, in 1899, Katherine E. McClellan said, "Yes."

At the time, she was a pioneering photographer who had settled in Saranac Lake to accompany her sister, who was curing there. She created the Katherine E. McClellan Studio, using her work to promote the beautiful wilderness of the area and create souvenirs she could sell at local attractions.

One of her creations was "A Hero's Grave in the Adirondacks," a 6 x 9 1/12-inch, 20-page illustrated pamphlet. It had been sold at the John Brown Farm since 1896. It is speculated that this popular keepsake was how she came to be contacted by Dr. Thomas Featherstonhaugh. He was a Washington, DC civil servant, an employee of the Federal Pension Office, and president of the Washington Humane Society, but was perhaps best-known as an avid scholar, collector, and admirer of the radical abolitionist, John Brown.

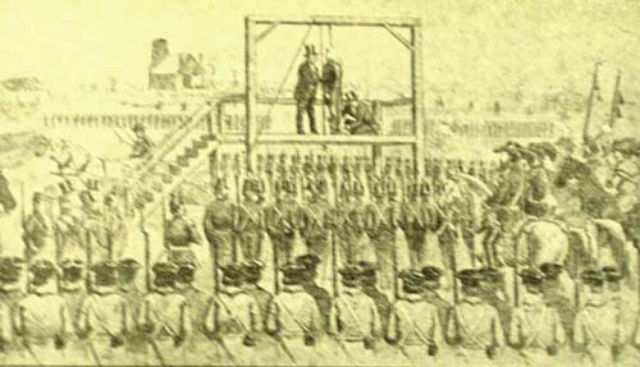

The events of October 1859 were still vivid in the nation's memory, especially since John Brown's ill-fated attack on the federal armory in Harpers Ferry was considered to be a major spark which ignited the flames of the Civil War. After a highly publicized trial, the penalty for John Brown and his surviving followers was death by hanging.

John Brown himself was the focus of an extraordinary funeral cortege that left Harpers Ferry that afternoon, December 2, and did not arrive at his farm until December 7. This event continued to be the subject of heated public interest, with mobs showing up at every turn, following the coffin as it journeyed from railcar to wagon, ferry to sleigh, until finally being laid to rest December 8, 1859. There was news coverage and speeches from abolition advocates. It was a huge media event.

The rest of his followers, known as his Provisional Army, did not fare nearly so well. Of the men executed with him, two of the bodies were given to a medical college for study, some were quietly claimed by relatives, and others were hastily interred on the banks of the Shenandoah River outside of Harpers Ferry.

The fallen men's disrespectful treatment greatly distressed Dr. Featherstonhaugh. As an avid student of the entire event, he felt these men had been harshly dealt with, even after death. He longed to reunite them with their leader.

Even if it was forty-three years later.

a final journey

Dr. Featherstonhaugh had found like-minded partners in this gruesome, yet respectful, endeavor. An important one was Professor Orin G. Libby, fellow John Brown scholar, and a nephew of one of the escaped Harpers Ferry raiders. In the course of his researches, Professor Libby had encountered a local man who revealed the location of this obscure burial place.

Shortly after their hanging and hasty interment, the Governor had yielded to Mrs. Brown's plea to retrieve her husband and sons. Oliver was quietly discovered and relocated to a grave beside his father. (Watson was to follow in 1882, retrieved from the medical college by a sympathetic Union surgeon.) The others rested inside two simple pine storage boxes, unmarked and unsung.

The events of The Raid were still considered a controversial subject. Feelings ran very high. They would have to be extremely wary of drawing any attention to their quest, for fear of having their quest prematurely publicized, legally blocked, being beset by relic hunters, or even becoming the cause of a riot.

Professor Libby wrote his future wife, Eva Cory:

“I expect to engage in a harum-scarum expedition which I don’t even dare tell you about till it is all done. You’ll probably read of it in the newspapers. I fancy even the country papers will have enough to tell you, even if my letter fails, what it is all about.”

This was how, on July 29th of 1899, Featherstonhaugh and his fellow enthusiast, L.A. Brandebury, found James Foreman. He was an elderly, magnificently white-mustachioed, man who had witnessed the mass burial. Grabbing his son Lewis and a set of shovels, the party was led to the soggy bank of the Shenandoah. “Two sunken places in the ground” let them orient their digging, and the boxes soon appeared, three-feet down.

The searchers found them in "remarkably good condition" considering the length of time and the closeness to the river's edge. The clothes had fared particularly well, with patches of coats and vests with the buttons still on. One of the vest pockets held two short lead pencils, sharpened and unused.

Their work was completed around noon, and the pertinent contents (mostly bones) were brought to Camp Hill, near the Summit House. There, secured with packing materials of cotton and excelsior, they were placed into the trunk Libby had brought for this purpose.

together again

The rescuers had acted not a moment too soon. Word traveled through town so swiftly that Dr. Featherstonhaugh, from a hilltop perch on Lightner's porch, wrote that it seemed like the whole town had swarmed down to the site on the riverbank. But the trunk, escorted by Professor Libby, was already headed out of town on a northbound train.

While a frantic press besieged Dr. Featherstonhaugh, Professor Libby responded to his friend's worries about secrecy, bypassing New York City and choosing transport through Albany, instead. At this time Katherine McClellan was alerted, via letter, that the trunk would be in the charge of a "Mr. Libby, (who) seems to be rather peculiar and erratic, but enthusiastic over this matter. He will want the bones sneaked into the ground and nothing said about it, but I want some decent ceremonies to attend the burial that will make the matter memorable and historic.”

“State of New York, County of Essex : Orin Grant Libby, State University, Madison, Wisconsin being duly sworn deposes that he did this fifth day of August, 1899 deliver, sealed, a packet containing the remains of...the party of John Brown, killed at Harpers Ferry on or about October 16, 1859...to A. Fortune & Co., North Elba, N.Y., undertakers of said town.”

Miss McClellan agreed, stating her task, “this astounding proposition, involving secrecy and risk...appealed to my imagination.” She felt the thrill of honoring Brown's fallen men, and she arranged for burial through local authorities, with the added touch of burial rites that evoked a national scope. She arranged for a military detachment from the nearby Federal barracks at Plattsburgh, courtesy of then Secretary of State Elihu Root. “I determined that no obstacle should deter me from giving these heroes the grand military funeral which would be a fitting climax for their sacrifice.”

By the time of the ceremony, the recovered bodies were joined by two others, Aaron Stevens and Albert Hazlett, who had been secretly buried in New Jersey. Their resting place in a simple cemetery was threatened by industrial expansion, and with the timing being so perfect, they were instead shipped to:

The John Brown Homestead, North Elba, Essex Co., N.Y.

Care Katherine E. McClellan

Chairman, Committee (Reinterment) of Arrangements

The Town of North Elba had appealed to the public to raise funds sufficient for a "handsome, silver-handled casket" for the formal reburial on August 30th, 1899. It was the forty-third anniversary of the Battle of Osawatomie, the Kansas skirmish that started the John Brown legend.

In the words of Dr. Featherstonhaugh himself:

“This whole matter is more a question of sentiment than one of science.” August 1, 1899

After her exciting time in the Adirondacks, Katherine McClellan returned to her alma mater, Smith College, to document their events, buildings, and campus, creating a dignified image of life there. In recognition of her work, she was given the title of “Official Photographer of Smith College” in 1912.

In 1913 she and her sister, Daisietta, moved to Sarasota, Florida. They developed a tract of land there, still known as McClellan Park. It was a striking design that discarded the usual grid approach, and created a community which was unique and inviting.

Katherine E. McClellan was always a pioneer. And, it seems, always devoted to her sister.

Discover our many historical attractions. Explore our flavors of dining. Choose your favorite kind of lodging.

Header photo: detail of the John Brown panel in The Kansas State Capitol, by muralist John Steuart Curry. Many delightful details from abolitionist-john-brown.blogspot.com, especially the series titled "The Second Harpers Ferry Raid: The Fate of John Brown’s Men." Great thanks to Bunk's Place for the thrilling looks at Saranac Lake history, and as always, the invaluable Historic Saranac Lake.

In related ADK haunting news:

Packages and Promotions

Valid Jan. 21

- Jan. 21

Valid Jan. 21

- Jan. 21

Pet Getaway

Voco Saranac Lake

Your dog deserves an Adirondack getaway too. Book our pet friendly hotel near Lake Placid welcomes every member of your crew. Book our Pet Package...

Valid Dec. 1

- Dec. 1

Valid Dec. 1

- Dec. 1

Linger Longer in Saranac Lake

Best Western Saranac Lake

Linger Longer in Saranac Lake at our supremely located property, Best Western Saranac Lake. Stay 2 nights or more and get 15% off!

Valid Jun. 20

- Sep. 7

Valid Mar. 12

- Jun. 30

Guided Nature Immersions - 10% off for Pre-Season Registration

Adirondack Riverwalking & Forest Bathing

Picture it now...you are wading the Ausable River on a warm summer day, feel the cool water against you, hear the sounds of the birds and the...

Valid May. 1

- Oct. 31

Valid Dec. 6

- Nov. 1

Zip and Whip Expedition

Farmhouse UTVs

Experience Outdoors and Farmhouse UTVs have teamed up to bring your family and friends the Adirondack adventure you've been waiting for....

Valid Jan. 16

- Mar. 31

Valid Jan. 16

- Mar. 31

Hotel Saranac Ski & Stay Package

Hotel Saranac

Stay & Ski Package Stay at Hotel Saranac and Ski Titus Mountain Day or Night Package Your room reservation includes one adult lift ticket....

Valid Jan. 21

- Jan. 21

Valid Jan. 21

- Jan. 21

Stay and Dine

Voco Saranac Lake

Receive a 50 dollar credit per stay to use in our Boathouse Saranac Lake Pub. Enjoy an exceptional dining experience with unparalleled views great...

Valid Jan. 16

- Mar. 31

Valid Jan. 16

- Mar. 31

Hotel Saranac Sled & Spoke Package

Hotel Saranac

Snowmobile Package Hotel Saranac and Sara-Placid Sled & Spoke have partnered so you and a guest can explore dozens of miles of ADK snowmobile...

Valid Jan. 21

- Mar. 31

Valid Jan. 21

- Mar. 31

Titus Mountain Ski Package

Voco Saranac Lake

Enjoy your stay at the award winning voco Saranac Lake which includes two adult lift tickets at Titus Mountain Family Ski Center. Additional...