Tucked into the woods, away from traffic lights and bustling shops and restaurants of Saranac Lake lies the peaceful, serenely scenic hamlet of Onchiota, NY. Close to the paradises of Buck Pond, Rainbow Lake, and Lake Kushaqua, Onchiota is home to a seasonal antique shop, historic homes, and the extraordinary Six Nations Iroquois Cultural Center, where every element of Iroquois culture, past and present, is celebrated, honored, and shared.

The center opened as the Six Nations Iroquois Museum in 1954, created by Christine and Ray Fadden and their son, John. A visit to this museum isn't simply about admiring artwork or politely peering at displays; it is a profound, immersive experience all thanks to the devoted, unceasing efforts of the Fadden family. Today, the next generation helps carry on Ray and Christine's original mission through two of John's sons, Don and Dave. They are a dynamic, welcoming, kind, funny, and incredibly giving family, sharing their knowledge, wisdom, artwork, and enthusiasm.

I spoke with John last fall during Native American Heritage month, and he was kind enough to share stories of the museum. In this blog, the first of a two-part series, we look at John's parents, the museum's founders, Christine and Ray.

Christine and Ray

If you look at an old map of the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation, you'll see names that are still widely seen around the area today. Names like Loran, Tarbell, and Chubb dot the map. Christine Fadden was a Chubb, born and raised in Hogansburg until the age of twelve. Christine's first language was Mohawk, and she helped her mother Louise make traditional baskets. Her talent and interest in arts and crafts would later play a significant role at the museum.

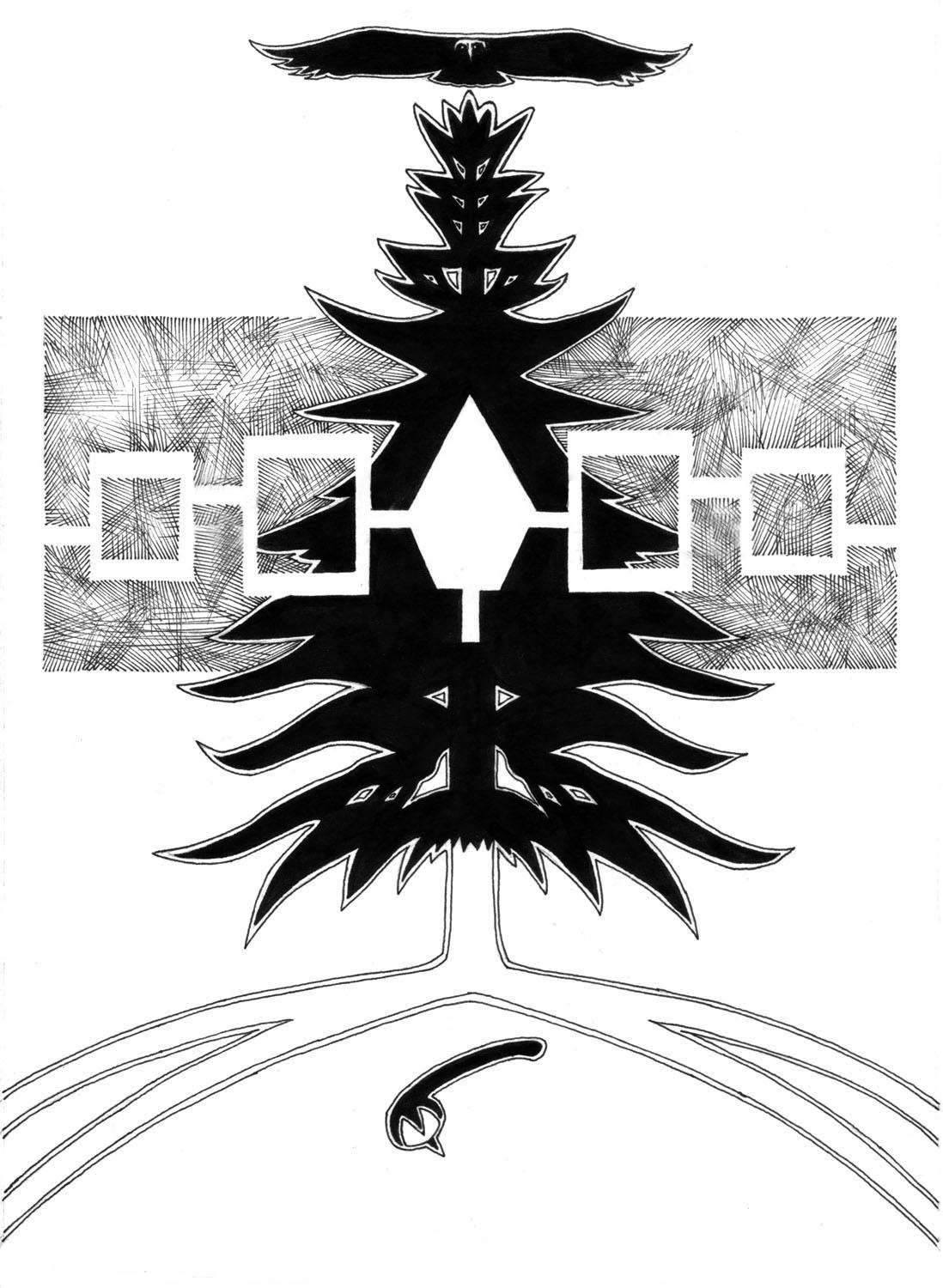

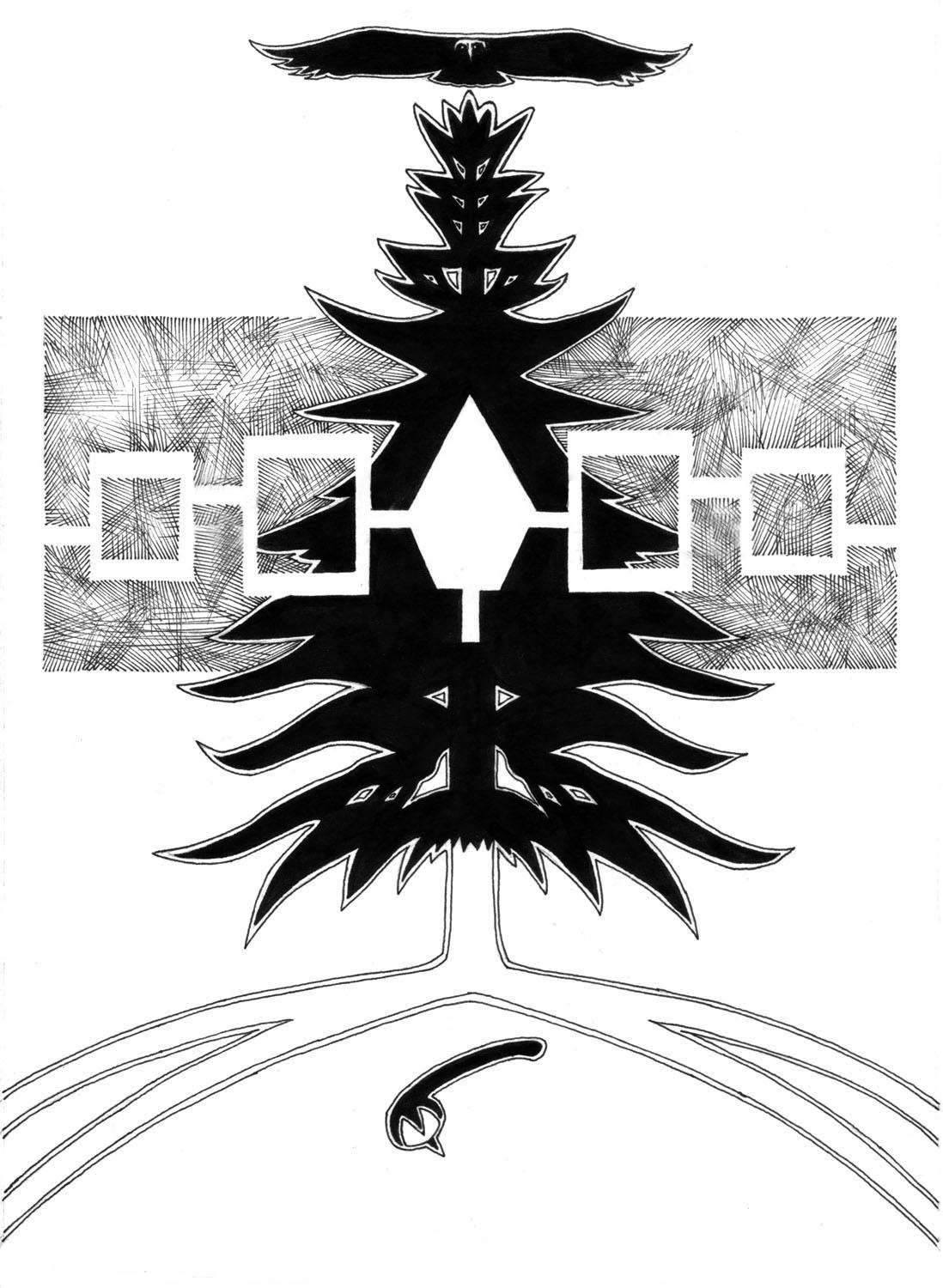

Ray was born in Onchiota in 1910 at his grandparents home. From the beginning, he loved nature, was a talented artist, and was profoundly fascinated by Iroquois history, crafts, and culture. He sought out elders from the six nations (Mohawk, Tuscarora, Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca, and Cayuga) that comprised the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy and learned as much as he possibly could. It was while teaching on the Tuscarora nation near Niagara Falls that he met young Christine Chubb. They married in 1935, and in 1938, their son John was born.

Even before the museum came to be, John recalls that Ray was busy. “He had a tremendous amount of energy. He was always doing something.” Ray taught at the Mohawk school in Hogansburg. John recounted that after school, Ray would take a nap before getting to work on various projects, including beadwork, which he did beautifully. The museum has a number of beadwork pieces that Ray crafted, including wampum belts and larger display pieces depicting important events in Iroquois history.

A connection to animals

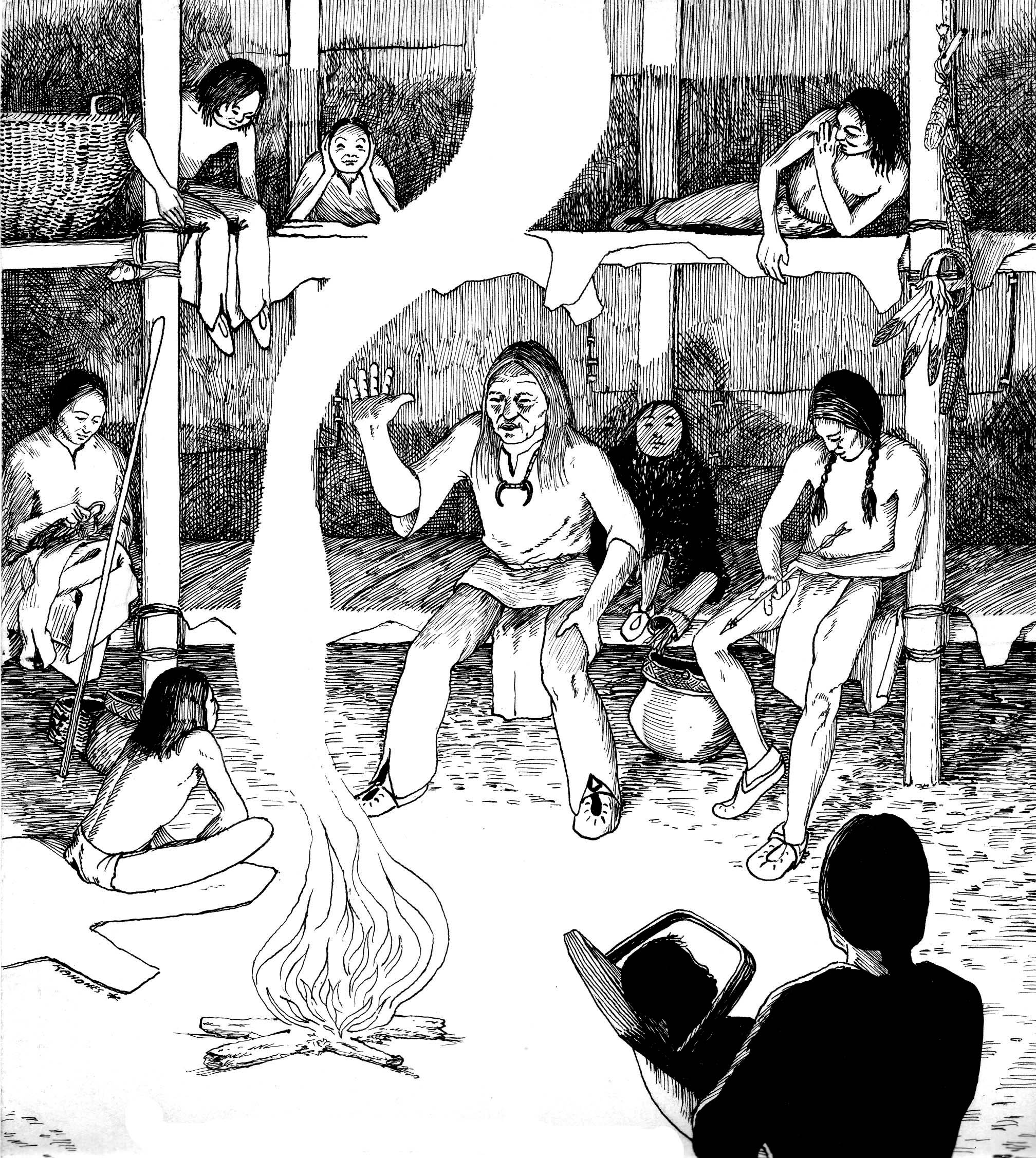

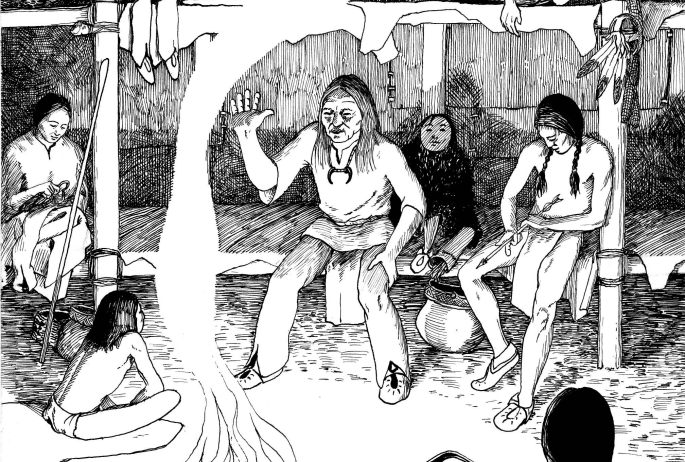

Ray always had a deep love for animals. From a young age, he had a deep interest in and connection to the natural world. He was also deeply interested in Iroquois culture, taking a job as school teacher at the Akwesasne Mohawk School. He loved animals, something that would continue throughout his life. As a boy he learned to mimic birds, which he would later include in his presentations on Haudenosaunee culture. “There is one particular Iroquois legend about how the birds got their songs," John says. "And he would relate that story and then in the process of it. When the birds got their songs, he would accompany those parts with these bird calls.”

For years, Ray also fed local bears. He started putting out scraps of meat, the bears started showing up, and they would return every season. Ray would collect scraps from a local meat market, and put the scraps on boulders in the woods for the bears. Ray became so familiar with the bears that he could tell them apart and once counted a total of nineteen individuals enjoying the feast he laid out for them. Coyotes and ravens would show up, as well, delighting the nature-loving Ray, whose interest in the forest was all-encompassing.

"He loved the woods. That's why we live out in the woods."

Early days and influences

Before the museum was created, Ray began producing educational pamphlets and charts on Iroquois legends, history, and culture, including the effects of colonial settlement. John was drafted to help; Ray would hand letter everything on bristol board, then John and family friend Bill Loran (who would go on to be an excellent craftsman of gustowehs, Mohawk headdresses) would "enhance" the charts with illustrations. Many panels with Ray's lettering and John and Bill's artwork are still on view at the museum today.

John credits his mother, Christine, with introducing him to an early love of art, writing, "When I was very young I had some plasticine clay, and I made a few things, rough in nature. My mother took the clay and made a human figure, and I recall being amazed by that. She taught me that, and I continued on in the field of art the rest of my life." Christine would play a major role in the museum's craft shop, which has always featured handcrafted Iroquois items, including baskets and beadwork. To this day, a visit to the museum begins and ends with that wonderful shop.

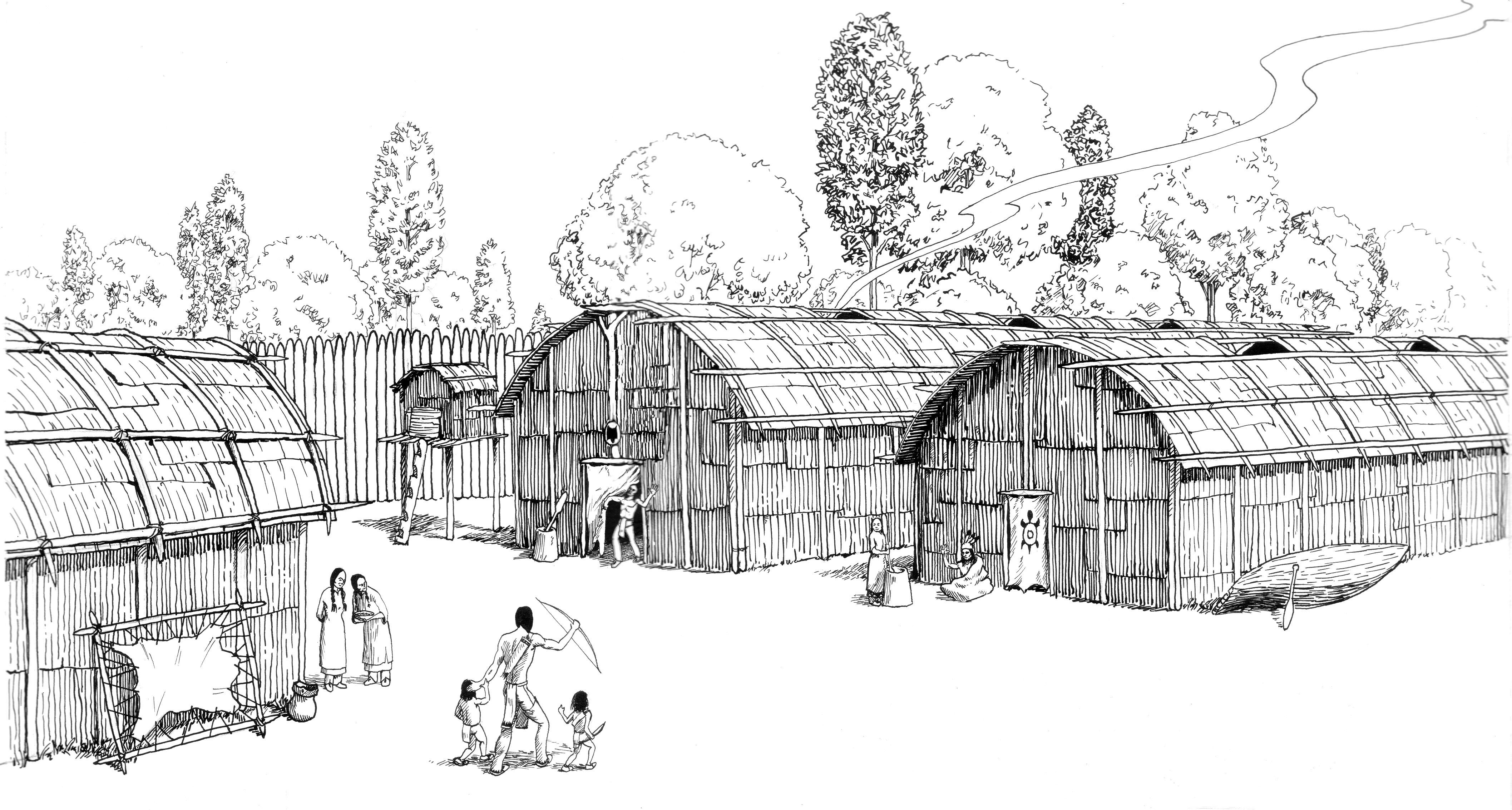

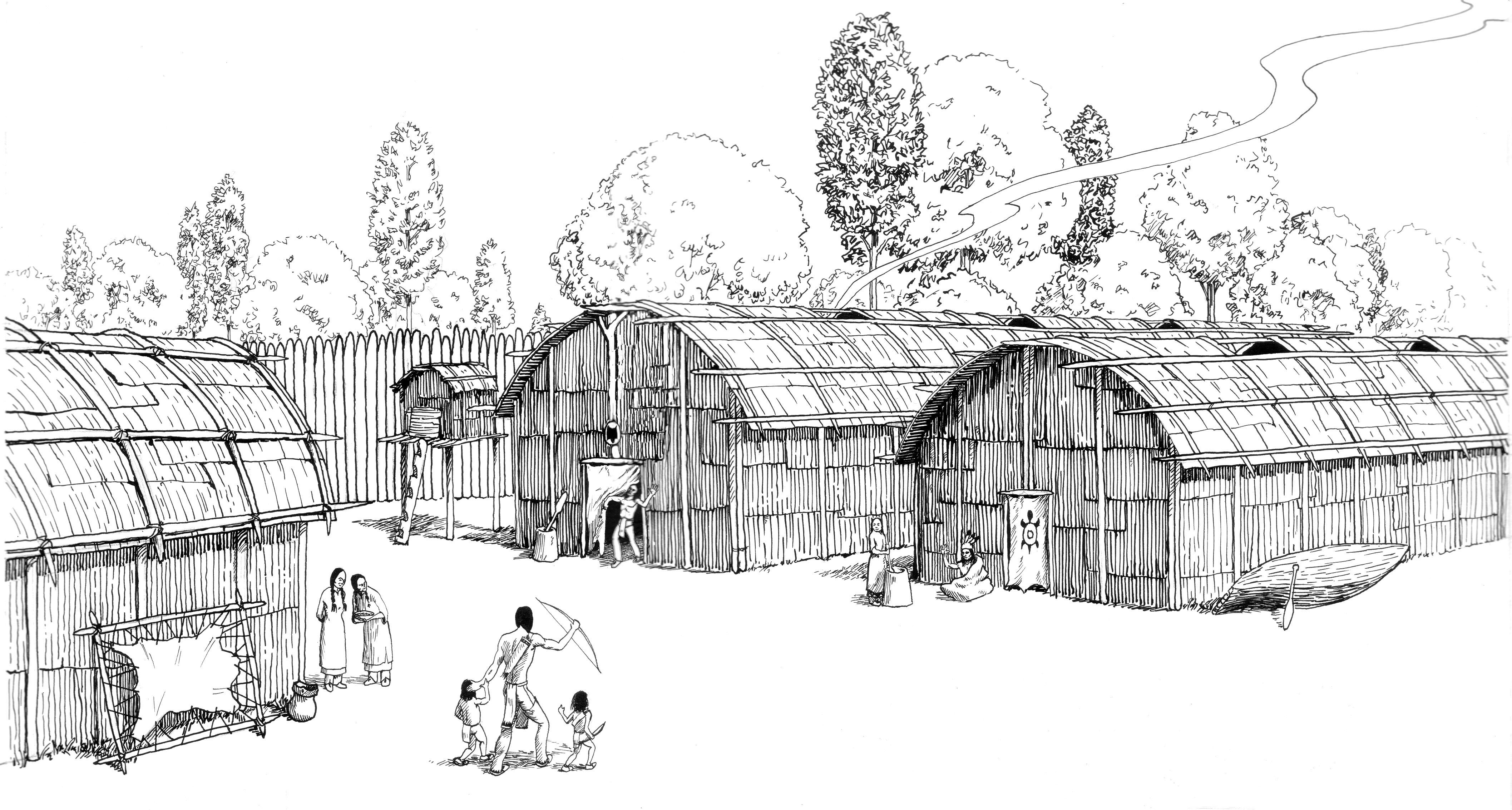

In addition to helping with artwork, the early days of creating the museum involved a lot of hard work for John, much of it out of doors, some of it less than fun. "Dad would get these ideas and we’d build lean-tos, we’d build a stockade fence. We made methods of storing food that was up above in the trees. There would be structures of the four corner poles going up with a dwelling on top, that’s where they would store food. These would be displays that would be on the museum grounds.” For wood, Ray would cut down small trees on their land for the wood, take the branches off, and John would carry them back. John jokes, “No matter what he did, he did just did it!”

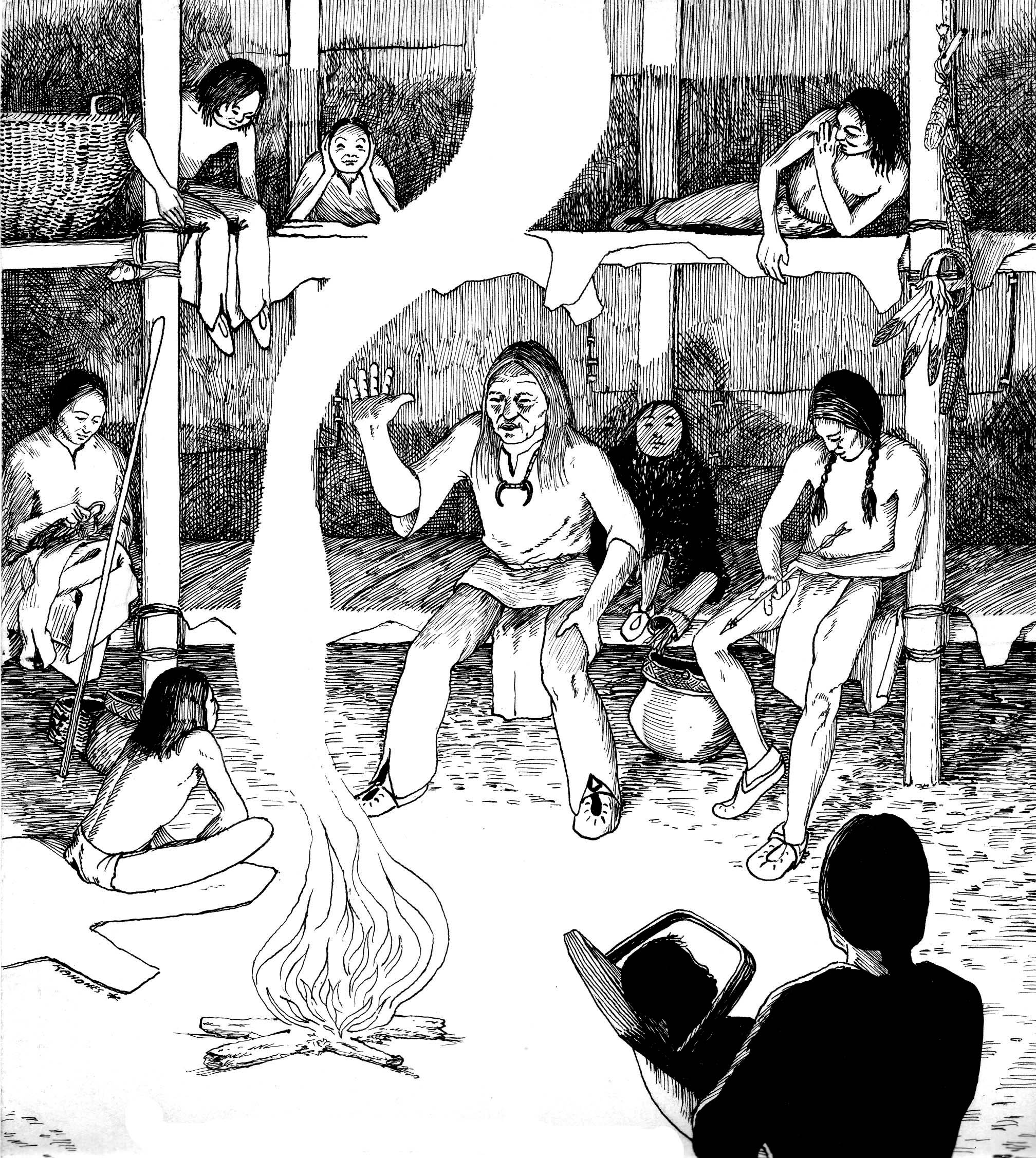

Part of the museum's ongoing mission involves teaching Iroquois traditions, including the importance of oral storytelling. For many years, Ray gave presentations and in the early days, John was his assistant, though sometimes his role was a little dull, explaining, "My father would have me tell some of these stories that are recorded on pictographic story belts. Either I would tell the story or I'd be delegated to help hold up those belts while my father told a story. That was an awful boring job, standing there!”

Joking aside, John's pride in his family's work is evident, though humble, whether he is sharing stories of his father's desire to travel and learn Iroquois history first-hand or chatting with visitors at the museum. John dreams about his parents at the museum, that they're all alive and together. It's a lovely thought, imagining all of the Faddens at the museum, together again.

Decades after Ray Fadden felled trees to be milled to build the museum, the design of which was based on the traditional longhouse, John and now his sons are continuing Ray and Christine's work, expanding the museum, educating thousands of visitors every summer, and providing a space for Iroquois culture to continue to flourish. “The driving force, of course, is my father. And it’s taken all of us to try to replace him.”

The Six Nations Iroquois Cultural Center is open Tuesday-Sunday, from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., in the months of July and August. On display are more than three thousand artifacts and works of contemporary art. Educational panels and charts relate Iroquois traditions, history, and culture, including foodways, the roles of cheiftains, and so much more. One or all of the three Faddens are always on hand to answer questions, explain story belts, and tell traditional stories.

To learn more about the museum today and the next generation of Faddens, stay tuned for part two in this series, coming soon! In the meantime, start planning your trip to Saranac Lake and Onchiota today!