African Americans have never made up large percentages in any census of the Adirondacks. However, they have been welcomed in proportions much greater than their numbers. Saranac Lake has long been supportive when it comes to the unique and profoundly difficult challenges faced by African Americans.

Depot on the Underground Railroad

The Champlain Valley to the east had been settled by a strong-minded mix of Quaker Pioneers and New England Yankees who held staunchly Abolitionist views, and tolerated black neighbors. Solomon Northup, of "Twelve Years a Slave" fame, was born a free person in Minerva, a part of Essex County, in 1808. Settlers carried these convictions into the forests and mountains of the High Peaks and Lake Country, providing fertile ground for the roots of the area's Underground Railroad.

Gerrit Smith was an early land owner in the Town of North Elba (which encompasses parts of both Saranac Lake and Lake Placid) who gave away 120,000 acres of farmland to approximately three thousand African Americans who lived in New York State. This experiment, known as Timbuctoo, was a short-term failure, as was a similar social experiment in Franklin County, Blacksville, started by Willis Augustus Hodges in Loon Lake. The settlers were primarily former urban dwellers with little experience in any farming, much less in the harsh conditions and daunting terrain of their 40-60 acre lots.

But long-term, some black settlers landed across five Adirondack counties. They included such prominent personages as Lyman Epps, a guide who cut one of the first trails to Indian Pass. He became a North Elba community leader who helped found the town library, school, and church. His family remained in the area for the next century.

It also brought nation-wide attention from like-minded others. Frederick Douglass helped recruit farmers on his famous lecture tours. John Brown, known for the raid on Harper's Ferry, had his own farm in North Elba. While his attempts to fan a nation-wide armed uprising were famously thwarted by his arrest and execution in 1859, this incident is considered to be one of the factors which led to the Civil War.

According to a historical account from 1918, the freedom-loving settlers of the area operated two main Underground Railroad routes; the more widely used being the one which ran to St. Albans, Vermont, and the other, even more secretive, went up to Malone and the Canadian border. The established group of black farmers in the area helped conceal the occasional fugitive from injustice. While most of the Underground Railroad's passengers went on to Canada, some families lingered in the Adirondacks. In the nearby farming community of Bloomingdale, the Alexander Hazard family made their home and left a "Hazzard" tombstone in the Pine Ridge Cemetery.

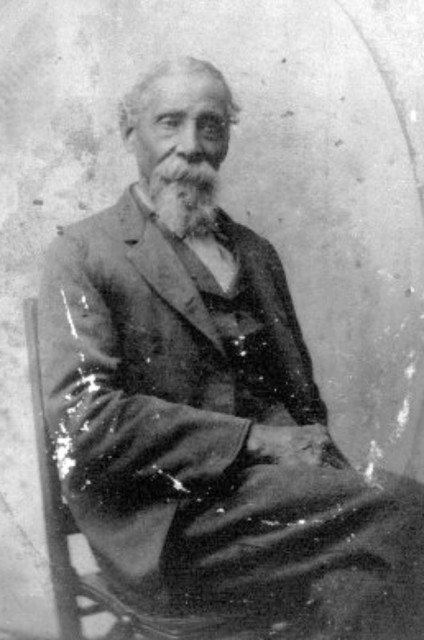

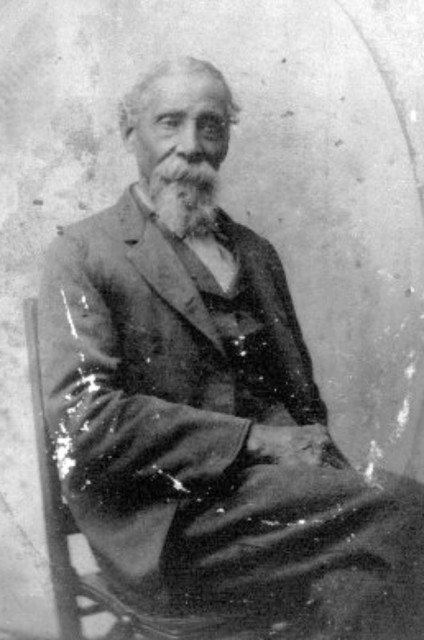

John Thomas was born into slavery in Maryland and was an Underground Railroad passenger. He took Mr. Smith's Timbuctoo offer of 40 acres in Franklin Falls in 1846. The story is told that when slave catchers showed up in town, local white men stated that not only was Thomas armed and willing to fight to the death, he would have the backing of many in town who were on his side. The slave catchers went away.

By 1872, he had accumulated a farm 200 acres in size, and was eulogized, in 1894, as "an honest, upright and fair dealing man, a good citizen" who was "much respected." There's an exhibit dedicated to his story at the North Star Underground Railroad Museum in nearby Chesterfield.

Logging legacy

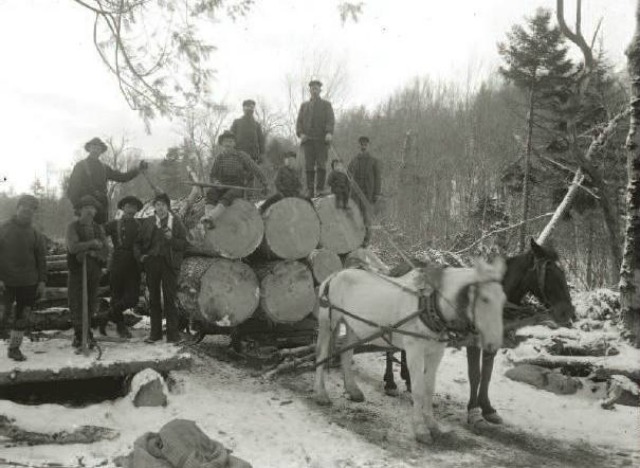

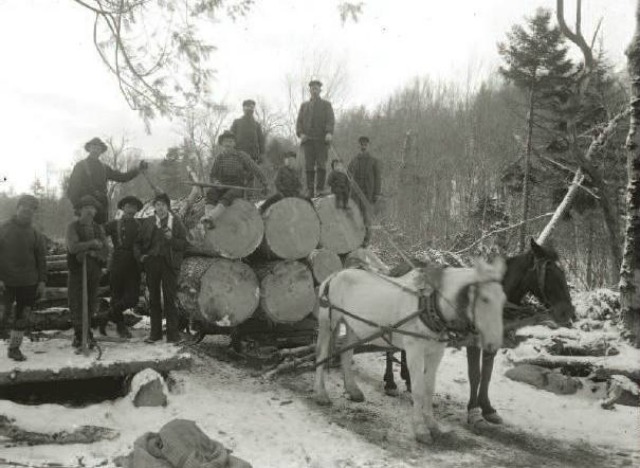

There is no record of any black loggers in the North Country, but this does not mean there weren't any. It took until 2009 for Gwen Trice to direct a documentary on the group of African-Americans from the South who became known as the "Maxville loggers." Some of them were her ancestors, and worked in northeast Oregon in the 1920s, yet were largely unknown until she began researching her family history. This encouraged current historians to discover African-American loggers in Michigan, Florida, and Washington.

So it's unlikely that there were no black loggers in the famous forests of the Adirondacks -- it's far more likely that they were there, but, due to the prejudices of the time, were simply overlooked and undocumented.

Lumber camps were famously rowdy places that welcomed strong backs and rugged outlooks from most of the ethnic groups in the United States of the time. In 1892, black laborers from Tennessee and the Carolinas were recruited to work in the railroading camps of the Adirondack & St. Lawrence Railroad, once clustered in the land north of Tupper Lake.

Welcomed for the cure

According to a recent documentary on tuberculosis, "The Forgotten Plague: The Deadly Story of Tuberculosis and the Hunt for a Cure," this disease had an extraordinary lethality. It has killed one out of seven people who have ever lived.

Ironically, the discovery that tuberculosis was caused by a bacteria offered the first hope of discovering a cure, but also a sudden new stigma placed on its victims. Patients were looked upon as sources of infection, and turned into pariahs in their home towns. But in Saranac Lake, the town-wide health regulations keep contagion to an extraordinary minimum, and people were not afraid. Everyone, from all walks of life, mingled freely with each other and with the townspeople.

Different cure cottages developed a reputation for cooking the food, speaking the language, and otherwise catering to the needs and preferences of certain kinds of clientele from all over the world. At Ramsey Cottage, black patients came from all walks of life; staff members from wealthy families, urban laborers and rural farm hands, and West Indians in need of a cure. Their Thursday night buffets were legendary, drawing chauffeurs and cooks and other servants from the Great Camps in the area.

Hall Cottage was the residence of Bill and Sadie Hall. While some of the history of their cure cottage is unclear, Sadie was part of the staff who served the wealthy Palmer family of St. Louis. The family moved to a mansion to be with a son who was curing. Their lady's maid set up separate housekeeping to allow her husband to work as a much sought-after caterer for well-off families in the area. Their home became a meeting place for all the black people of the village, patients, and townspeople alike. They are universally remembered as people whose hearts and home were open to all. For years, their New Year's feast was open to everyone in the neighborhood.

In other states, the races were strictly segregated in curing facilities, even though health officials knew all citizens would have to be treated in order to curb the White Plague. But in Saranac Lake, this was not a practice, no more so than the other cure facilities which catered to those with a background from Greece or Italy, factory work or show business. In fact, because of Dr. E. L. Trudeau's humanitarian outlook and worldwide reputation, many prominent doctors and scientists trained in Saranac Lake. They then carried this egalitarian attitude into their work in other parts of the United States, demanding equal treatment for all their patients.

Part of our heritage

Due to our unique setting, our towns remain small, and our citizens sporadically diverse. So it's all the more amazing that so many do seek out our little town with the big history.

Some linger for a week or a weekend, some for longer, and some wind up settling here. Which suits us fine. We are known for our hospitality!

Choose a favorite place to stay and dine and play. The elements that have pulled people here for a couple of centuries are much the same, such as our incredible wilderness. And our desire to care about you.

Header photo is courtesy of The Adirondack Museum, Blue Mountain Lake, New York. The photo was taken in South Carolina by photographer E. T. Start, who spent winters in South Carolina and summers in the Adirondacks. Much of the research in this blog came from the amazing wiki maintained by Historic Saranac Lake. Some very obscure facts about African-American logging were first published by The Adirondack Almanack.